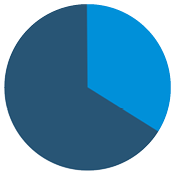

Our global food system generates 34% of global CO2 emissions.

Food sovereignty is the pathway to a climate-friendly food system.

Food sovereignty means growers, distributors, and consumers decide how our food is grown, where it ends up, and who has access to it.

Reaching food sovereignty means all people have access to healthy, affordable foods of cultural significance that are produced with respect for the land and the people working to get food from soil to plate.

Courtney Grimes-Sutton

Barnstormer, Bridge Builder, Pyrokinetic

Butcher/Farmer, Mace Chasm Farm

Courtney runs Mace Chasm Farm, a diversified livestock operation in Keeseville, NY, with her partner, Asa Thomas-Train. They practice rotational grazing, a sustainable farming method that shifts animals to different parts of the pasture. This allows the land to rest and regrow between grazings. They also incorporate silvopasture techniques, a practice that plants trees on pasture land. This stores carbon and increases plant and animal diversity. These trees can also provide food for humans and livestock.

Birch Kinsey

Pro-Bell Pepper, Anti-Zucchini, 5’10”

Farmer, Youth Activist

Birch is a youth activist working to heal the land through regenerative farming practices. She strives to build spaces where humans and nature thrive together. She has been farming since the age of 14 and has been part of local food movements that help create healing spaces for farmers of color. She is an integral part of the Massachusetts Avenue Project, an urban farming project in Buffalo, NY, that reconnects local youth with the land and works to create an equitable, accessible, and climate-friendly food system.

Watch

Astrid St. Pierre

Tree Person, Lover of Wind, Rollerblader

Student Activist, Lake Placid High School

Ellen Lansing

Sky Lover, Wearer of Clothes, Aspiring World Traveler

Student Activist, Lake Placid High School

Astrid and Ellen are high school students who started a nonprofit composting operation, Placid Earth. This student-run organization turns food scraps into soil. They collect food waste from local schools and businesses and load it into their industrial-size composter, which they named Joel. In their first two years, they diverted over 20,000 pounds of food waste from the community of Lake Placid, NY, creating soil used to grow more food.

Listen

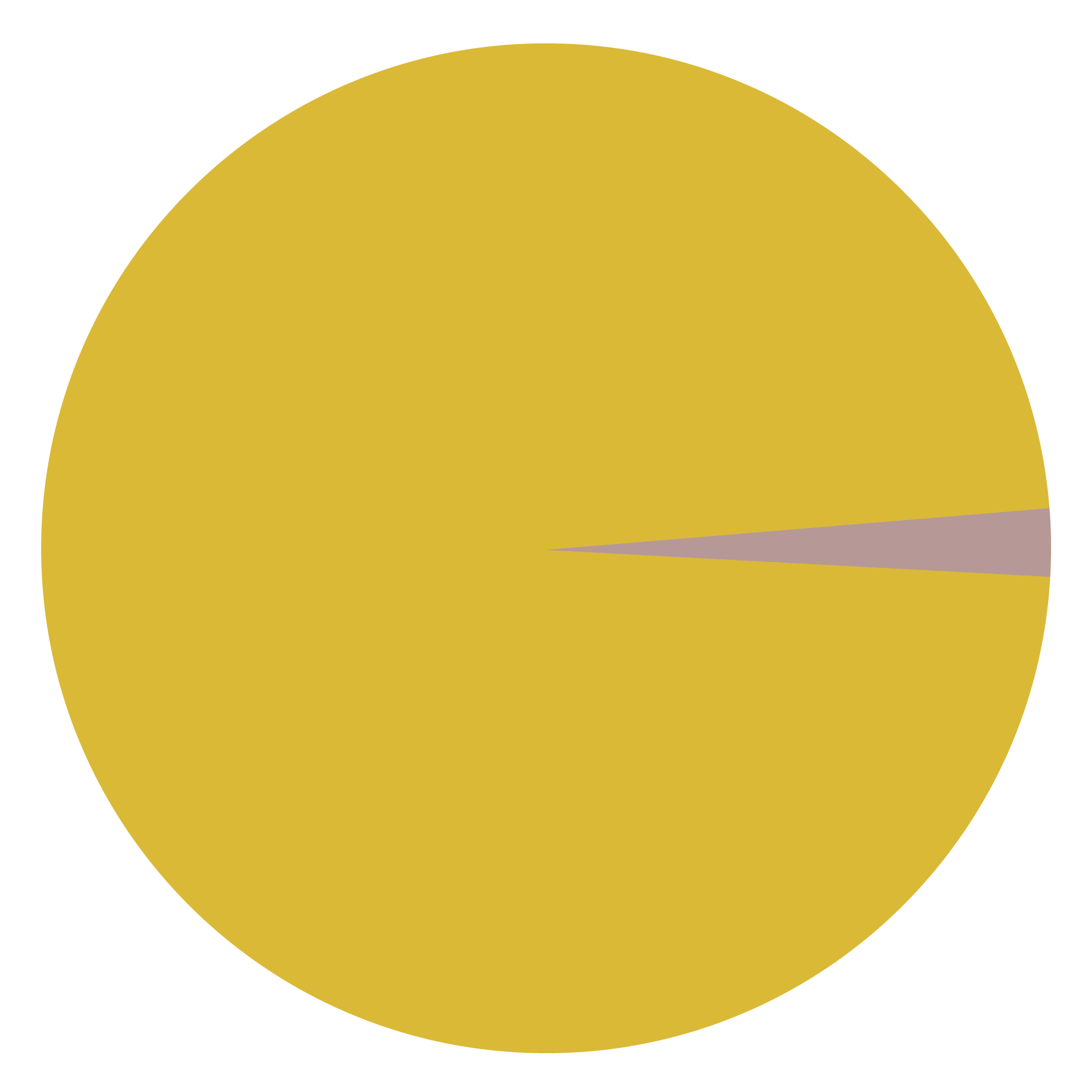

As much as 40% of our global food supply is wasted.

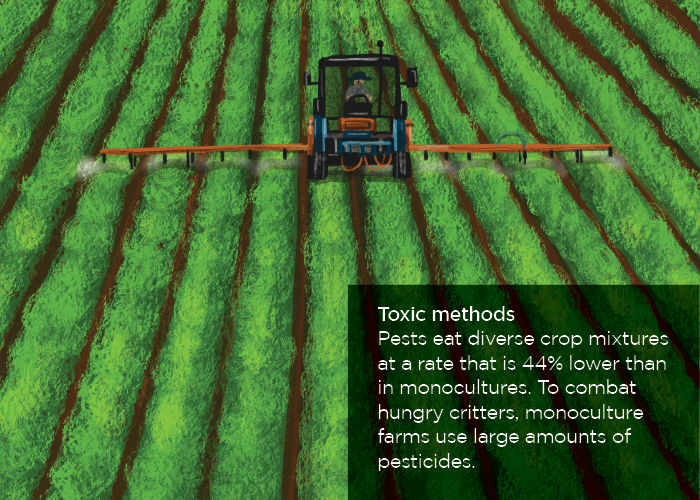

Around 30% of food waste in the U.S. starts on the farm due to imperfections, overproduction, spoilage, harvesting labor shortages, and poor storage. The rest gets thrown away by grocery stores, restaurants, and consumers.

Choosing imperfect foods, buying only what we can eat, being flexible with “best by” dates, finding creative ways to use up old ingredients, and composting inedible food scraps can all help eliminate food waste on the consumer level.

Reducing the amount of food we throw away will lessen carbon emissions, feed more people, and reduce landfill loads.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) reflects generations of observations, experiences, and practices held by Indigenous peoples in a specific place. This knowledge recognizes that everything is interconnected; it is practiced by being in constant conversation with the land. This perspective results in a deep, holistic understanding of natural systems, and is deeply rooted in cultural practices.

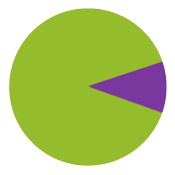

Putting our seeds in many baskets. Seed saving is the act of planting and collecting seeds from the healthiest plants year after year. This practice, rooted in the traditional knowledge of many different cultures, carries multiple benefits: it preserves crop diversity and maintains the ability of crops to withstand changes in growing conditions.

This practice is hyperlocal. Each plant is adapted to its specific location and climate, and doesn’t rely on pesticides or herbicides. That makes the plants better able to respond to environmental changes such as drought, pests, increased rainfall, and changes in soil composition.

The Wild Center is grateful to Katsitsionni Fox and Sateiokwen Bucktooth for sharing these ways of knowing:

Katsitsionni Fox

Visual Storyteller, Pot-Maker, Future Ancestor

Artist, Filmmaker, and Community Educator

Katsitsionni shares her knowledge and the experiences of Indigenous women through art and film. As a seed saver, she also shares her knowledge of heirloom seeds and the cultural significance of these seeds with the youth in her community. Every year her extended family gathers to plant gardens of heirloom seeds.

Sateiokwen Bucktooth

Plant-Lover, Kayaking Enthusiast, Karaoke Singer

Owner, Snipe Clan Botanicals

Sateiokwen Bucktooth is a Traditional Ecological Knowledge consultant for the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe’s Environment Division. She also owns Snipe Clan Botanicals, a shop offering herbal medicines and beauty products made with many locally grown, foraged ingredients. As a healer, Sateiokwen works to reconnect indigenous communities with the traditional knowledge of medicinal healing.

How can we rebuild out food system in a way that gives more people access to farmable land? Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) groups have been systematically excluded from land ownership in the United States. This exclusion started with the enslavement of Black people and national- and state-sanctioned theft of land once cared for by Indigenous peoples. When we support policies and practices that return lands to BIPOC farmers, we help to make our food system more inclusive.

98% of private farmland in the U.S. is owned by white farmers.

Hover over a vegetable to find out.

Sliding Scale Payments

More farms are beginning to offer flexible payment options and pay-what-you-can-afford prices for fresh produce and meats.

SNAP

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provides fresh foods to those in need. This federal program offers seeds to farmers and partners with growers to allow participants to purchase local foods at farmers markets.

Farm-to-people

Many farms throw away edible food due to overproduction, imperfections, and labor shortages. New programs can move this excess food from farms to local food banks. For example, Cornell Cooperative Extension collects excess food from Hudson Valley farms and delivers it to soup kitchens, food pantries, and community organizations.

National Farm to School Network

The National Farm to School Network connects local growers with schools, providing fresh, healthy foods to kids. Students are also introduced to school gardens, working farms, and cooking through this program.

Farmworker’s Rights

Food accessibility starts with supporting the people who grow our food. Four out of every ten farmworkers lack access to healthy, affordable food for themselves and their families. Supporting farm workers includes addressing food insecurity, discrimination, low pay, long hours, exposure to pesticides, extreme heat, and other unhealthy working conditions.

How can we make farming more accessible to everyone?

White-led agricultural corporations have historically determined how we grow our food, who grows it, and who has access to it. Overhauling the food system for people and the planet requires equitable financial support for land and farming tools, and access to farming knowledge and assistance. This transition can start through policy changes and educational programs.

10.5% of households lack adequate access to food.